CO Updates Home | Archive: 2022, 2021 |

December 20, 2021

By Stephen E. Marcus, PhD, MPH, Scientific Program Manager

Stephen E. Marcus, PhD, MPH, Scientific Program Manager

After a 35-year career in public service, Dr. Stephen Marcus, HSR&D Scientific Program Manager, will be retiring in December. Here, Dr. Marcus reflects on “lessons learned” throughout his journey from early academia to VA Central Office, where he oversaw the HSR&D Access, Complementary and Integrative Health, Education, Health Care Organization and Implementation, Randomized Program Evaluations, Research Methods Development, and Systems Modeling, Design and Delivery, research portfolios.

During the course of my career, I’ve really noticed that there is a considerable amount of reinventing the wheel in health services research. Each new discipline and each new generation of researchers tackles the same big questions and rediscovers many of the same things. As this great article from 2005, “Health Care Reform and Health Services Research: What Once was Old is New Again, and Again” highlights, the conceptual models may get more sophisticated, and the methods may improve, but too many times we are still picking and selling low-hanging fruit. So, the key lesson here is, revisit the past so that you can innovate in the future.

My second piece of advice also looks backward, and that is: Start reading every bit of Donabedian you can. He was truly the greatest and humblest scholar and synthesizer I have ever met. He once told me a very personal and powerful story—he said that the students who took his courses and were the most critical of them were those in Hospital Administration. They complained that his teaching was too abstract and irrelevant to the day-to-day realities and grind of the trenches. Ironically, he also said that these same students often came back to visit him years later, after being out in the “real” world, to express appreciation for what he had offered them years earlier: a conceptual foundation to understand how things could be improved. Stepping back from the trenches, if only for a short while, they grabbed on to what he had taught them for guidance on how to reimagine and restructure what they knew was dysfunctional.

My third piece of advice looks forward. Complex problems are not solved with simple conceptual models or methods, but rather require the sort of holistic complex system science and computational approaches that are at the forefront of research today. The more we can be open to and communicate the value of modeling “what-if scenarios,” the greater and faster the progress we will make. We have reached impasses in many areas, from access to health disparities, that can be overcome with the application of complex systems and computational thinking and tools. This is because reductionist approaches to these complex problems can only yield limited insights in the context of dynamic systems. Analytical methods that focus on identifying independent effects have hampered progress and constrained even the types of questions being asked and solution sets proposed. Understanding how dynamic relationships between factors at different levels of organization result in the emergence of phenomena is key. There is also exciting progress integrating machine learning (from computer science) and causal inference (from epidemiology, biostatistics, and quantitative psychology). When I attended my first AcademyHealth annual conference in 2019, after many years away, I was pleased to see how many of the methods sessions were at the cutting edge of these areas and within the past year, HSR&D has funded several initiatives that have embraced these approaches.

These lessons have served me well, and I hope that the HSR&D research and administrative community may find them useful as well. It’s been a terrific experience serving this team, and I wish you all the best for future success.

November 17, 2021

By Maciej Gonek, PhD, AAAS Science & Technology Policy Fellow

Maciej Gonek, PhD

Most people with SARS-COV-2 infection recover within weeks of illness, but a substantial minority experience a wide range of new or ongoing health problems lasting far beyond the expected duration of COVID illness. This phenomenon first came to attention through patient self-reports on social media and was dubbed “Long COVID” but in the official terminology of WHO and CDC it is now covered by “post-COVID conditions.”

HSR&D and the other ORD research services have expressed a keen interest in quantifying and understanding the long-term outcomes of Veterans with SARS-COV-2 infection, the mediators and underlying pathophysiology, and developing effective clinical interventions. In August, HSR&D hosted an External Stakeholder meeting that brought together leaders from current ongoing VA projects as well as clinical partners and representatives from other government agencies to share knowledge about current efforts and establish direction on certain priorities. The priorities identified included cognitive impairment, mental health, persistent fatigue, influence of different viral variants, and functional impairment. Currently, Long COVID clinics have been established in multiple VA Medical Centers to support patients who experience lingering symptoms months after initial diagnosis of the illness. Future endeavors will include connecting these clinics with the leads of ongoing projects to share knowledge and elicit alignment on data collection.

As many unanswered questions on the etiology and management of Post-COVID conditions remain, last month ORD released a program announcement for upcoming merit review cycles describing the specific priorities for each ORD research service related to Post-COVID conditions. On November 11, ORD released a cross-service Post-COVID Conditions Collaborative Merit Award (VA network access only). This opportunity allows investigators to submit individual applications as part of a group of 3 I01 projects that address a clinical or scientific issue relevant to Post-COVID conditions. We hope this new funding mechanism will allow fruitful new collaborations to accelerate our understanding of Post-COVID conditions by allowing investigators with different expertise to examine different aspects of a single, high priority problem. Just as important, this effort may serve as a prototype for encouraging cross-ORD research collaborations on other important problems facing Veterans.

October 19, 2021

By Amy Kilbourne, PhD, MPH, Director of QUERI

Amy Kilbourne, PhD, MPH, Director of QUERI

VA/HSR&D’s Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) recently held its Annual Strategic Meeting to discuss how to align its priorities with the needs of Veterans and the VA healthcare system. With more than 200 investigators, 50 centers, and 70 VA leadership partners across the country, QUERI works to implement and evaluate programs at the clinic level that address VA national priorities. Therefore, a significant part of this meeting with stakeholders – including VA senior leadership, VISN directors, chief medical officers, and chiefs of staff – focused on answering the question posed by QUERI Director Amy Kilbourne, PhD, “What keeps you up at night?”

We need to examine the impacts of the pandemic on this health system as we move forward, including Long (or Post) COVID-19. For example, how did deferred or delayed care impact Veterans? How do we ensure that our Veterans have access to the care they need? Also, when we think about the effects of the pandemic, we need to consider the effects on our workforce. Not just the clinical workforce, but VA support staff at all levels. —Mark Upton, MD, VA Acting Deputy Under Secretary for Health

As Integrated Veteran Care (IVC) rolls out, we will need to evaluate the variations among VA facilities and community care. This will be a critical need in the future. In the near term, we need an evidence checklist and a framework to evaluate whether an innovation actually makes a difference for our patients and the VA healthcare system. —Carolyn Clancy, MD, Deputy Under Secretary for Health for Discovery, Education, and Affiliate Networks

We need to look at efficiencies in our workforce – workload, burnout, and expansion issues that may affect capacity to meet the needs of the increase in Veterans that are forecasted. Assess inefficiencies in how we deliver care and identify how to address them. We need to become more efficient across the board so we can increase our capacity —Kameron Matthews, MD, JD, FAAFP, Assistant Under Secretary for Health, Clinical Services

How do we empower patients to be stewards of their own health? How can the systems we have in place be treatment engagement vehicles? Patient empowerment and treatment engagement will help Veterans better navigate both VA and community care. — Thomas O’Toole, MD, Deputy Assistant Under Secretary for Health, Clinical Services

I’m concerned about getting a handle on preventative care, which lagged during the pandemic. The private sector is dealing with the same. It’s also difficult to access care in the private sector for our Veterans, including limited resources for mental healthcare and rehab services. —Skye McDougall, MD, VISN 16 Network Director

What keeps me awake at night is the rural workforce problem. It’s not about technology, it’s about keeping healthcare workers in rural areas. The rural workforce is getting older. In the next few years, there will be a 25% reduction in physicians based only on aging out. Some of our workforce has also left rural areas due to the pandemic. And it’s not just VA losing rural workforce, private hospitals and clinics in rural areas are closing and their staff are leaving rural areas and choosing to work in hospitals in the cities. —Thomas Klobucar, PhD, Director, Office of Rural Health

September 17, 2021

By David Atkins, MD, MPH, Director of HSR&D

David Atkins, MD, MPH, Director of HSR&D

VA research owes a heavy debt to VA’s early investment in electronic health records. The 20+ years of electronic health record data that make up the corporate data warehouse (CDW) has supported national studies of variations in clinical practice and outcomes, the equity of care and health outcomes across different Veteran groups, and the implementation and spread of new practices. Big data innovations developed under clinical programs have also used this data to develop clinical prediction tools such as the CAN score for high-risk patients in primary care,1 the suicide risk prediction instruments used in REACH-VET,2 and the STORM model for risk of adverse effects of opioid use.3 The COVID era has stimulated additional work on predictive models using big data – two COVID risk models have been developed by ORD-funded researchers and the VA’s National Artificial Intelligence Institute has piloted AI (artificial intelligence) developed models for predicting poor outcomes.

As the collapse of Amazon’s venture Haven points out, it is one thing to mine data to make predictions but an entirely different challenge to turn those insights into savings or better outcomes. Healthcare is a complex social system with multiple influences on behavior and actions. The pressing opportunity for VA research is to show how to apply insights from big data into better care for Veterans. For models to improve care, we need to establish three conditions, which in turn help define a research agenda: 1) The model must be accurate and reproducible; 2) the information provided needs to improve on clinical judgment, influence clinical decision, and improve health outcomes (or reduce costs while maintaining outcomes); and 3) the model needs to be implementable at scale across the VA healthcare system.

Reporting and Validating: Typically, the discriminating power of a predictive model is reported as Area Under Receiver Operating Characteristic (AUROC), but this may exaggerate the value of models predicting rare events such as death from COVID. Other ways of characterizing accuracy include the Area Under the Precision Recall Curve (AUPRC). Researchers usually validate predictive models by rerunning a model on an independent set of data, which is not possible for models in VA that often use 100% of the relevant data to build and refine the model. We need to advance methods for reporting and validating the types of models used in VA with national data.

Testing effects on decisions and outcomes: Predictive models may be accurate, but to add value they need to improve clinical judgment. Being able to accurately identify the very highest risk patients is rarely what adds value since clinical judgment is often good at flagging those patients at the top of the risk stratum. More useful is improving our discrimination among those at moderate risk; for example, determining when a mental health patient or a COVID+ patients be safely managed at home. Testing whether such models change clinical decisions is one important step, but documenting an effect on clinical outcomes is difficult since many of them (i.e., drug overdose, suicide) are infrequent.

Examining Implementation: Research is needed on how to effectively implement models in practice. The first challenge is a computational one: Models based on complex algorithms with hundreds of data elements require substantial computing power, making it impossible to run in real time. For those that don’t depend on real-time data, such as CAN and STORM scales, they can be updated regularly and pushed to clinicians. But a predictive COVID model incorporating contemporaneous lab or vital signs may be impractical to run in real time in a busy emergency department. An alternative is to convert models into simplified risk scores that can be calculated from a subset of the most important data, as was done for the VACO risk score.4 Implementation studies are needed to identify barriers and solutions to implementing these tools at scale.

VA is ahead of much of the country in the quality of its data and the use of tools derived from that data. Research needs to ensure that these and future tools fulfill their promise of improved care and better health outcomes for Veterans.

References:

August 16, 2021

By Robert William O'Brien, PhD, MA, Scientific Program Manager for Mental and Behavioral Health

Robert William O'Brien, PhD, MA, Scientific Program Manager for Mental and Behavioral Health

A great deal of my focus these days is on promoting and supporting the work of HSR&D investigators working on research to reduce suicide among Veterans. The invitation to write this Note offered me a chance to reflect on how this area of study has changed over the years. When I joined VA in 2010, there were 17-18 Veteran suicides per day (revised from the original estimate of 21 suicides per day), but a hard focus on this area was still missing. During Fiscal Year 2010, HSR&D supported 5 research studies and 1 Career Development Award (CDA); however, those 5 studies may have built the foundation for what was to come. All but one of the funded projects, plus the CDA award, were led by investigators who are current leaders of the suicide prevention research field within HSR&D/ORD/VA. The total investment in these 2010 projects was $3,418,206.

Fast forward 10 years to FY2020, and the estimated number of daily suicide deaths among Veterans is basically unchanged, although continued increases in the general populations suicide rate means that Veterans constitute a declining proportion of all suicide deaths across the U.S. Within HSR&D, during FY2020 there were 23 funded suicide prevention studies, (including 3 QUERI projects, 2 Innovation Projects, and 2 projects receiving COVID-19 Rapid Response funds), as well as 2 CDAs and a new Consortium of Research (CORE). The total investment in these projects was $22,782,780, almost 7 times greater than the funding awarded in FY2010.

VA’s response to the suicide crisis has been remarkable, and this includes a tremendous effort on the part of the HSR&D research community. HSR&D studies have supported a number of key areas:

Our research efforts also are strengthened by responses to the National Research Action Plan, multiple Executive Orders, as well as new interagency collaborations, such as VA partnering with the National Institutes of Mental Health and the Department of Defense to support the Department of the Army’s Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (STARRS) Longitudinal Study. Moreover, HSR&D has made a key investment in the Suicide Prevention Research Impact Network (SPRINT) CORE. Among many roles, SPRINT funds small, developmental suicide prevention studies; serves as a research resource for investigators in the field generating new, innovative proposals; facilitates dissemination of research findings; and is building important collaborations with VA investigators, other parts of ORD, and VA’s Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, as well as with multiple federal agencies. We anticipate that over the next few years, SPRINT will grow in importance as a strong foundation for all of VA suicide prevention research. To close the 10-year circle, SPRINT’s leadership team now includes several of those investigators who were among the few funded way back in 2010.

Thinking back, very few of the steps taken in 2020 were even being considered in 2010, either in HSR&D or in other offices around the VA. HSR&D remains confident that efforts to reduce daily suicide numbers down will be strengthened by investigators looking to break new ground in suicide prevention research.

July 21, 2021

By Naomi Tomoyasu, PhD, Deputy Director of VA HSR&D

Naomi Tomoyasu, PhD, Deputy Director of VA HSR&D

Although COVID has profoundly impacted us, the good news is that things appear to be slowly and cautiously returning to normal–or at least the new normal. Health services research has continued to march ahead with resilience and might despite the pandemic. However, COVID has highlighted again the health disparities experienced by Veterans from communities facing discrimination and who are otherwise under-represented. What is hopeful is that notable positive changes have been occurring at the national level and new and exciting Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) programs have been launched!

First, the White House released an Executive Order which establishes a government-wide initiative to advance diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility in all parts of the Federal workforce. Led by the Office of Personnel Management and the Office of Management and Budget, in partnership with the White House and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, this Initiative will advance opportunities for communities that have historically faced employment discrimination and professional barriers, including: people of color; women; first-generation professionals and immigrants; individuals with disabilities; LGBTQ+ individuals; Americans who live in rural areas; older Americans; parents and caregivers; people of faith who require religious accommodations at work; individuals who were formerly incarcerated; and Veterans and military spouses. We’ve been making great research strides with many of these groups and will continue to do so in the coming months and years.

In alignment with the Executive Order, there are also several noteworthy changes that will promote and support DEI activities within ORD. One significant event is the launch of a formal ORD-wide Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Workgroup with a clear mission statement, a charter, and a Stakeholder Engagement Board that will provide recommendations to enhance DEI research and recruit and retain a more diverse workforce. A significant characteristic of this workgroup is that it has been backed with funds from the Chief Research and Development Officer, Dr. Rachel Ramoni. Close to $2.5 million has been committed to this DEI effort within ORD, including support to research supplements to 10 outstanding early career investigators from under-represented groups and their mentors. Of the 10 applications awarded in the program’s first year, 4 were awarded to HSR&D researchers! This highlights the extraordinary pool of senior and early career investigators in health services research who were successfully able to achieve these funds due to their deep commitment and expertise in DEI research.

Another noteworthy event is the launch of the first HSR&D DEI workgroup to increase representation of under-represented groups, including racial/ethnic minorities, specifically in health services research. The work of this group has already led to several accomplishments this year including a training and career development program started this summer by HSR&D’s Center for Healthcare Organization and Implementation Research (CHOIR) (led by Dr. Keith McInnes) for medical students from under-represented racial and ethnic groups in partnership with the Boston University School of Medicine. In addition to the ongoing DEI training and projects that workgroup members have already launched locally, the workgroup also has begun a series of interviews (led by Dr. Christine Hartmann) to assess the experiences, insights, and opinions of researchers and staff from under-represented ethnic/racial minority groups within VA. An additional objective of these interviews is to identify barriers and facilitators to retention of racial and ethnic minority researchers focusing on both interpersonal and structural factors that may benefit some groups more than others. Based on the recommendations of this workgroup, HSR&D will also initiate new mentoring and training opportunities and develop new or enhance existing research funding mechanisms that highlight the importance of diversity in health services research.

Lastly, this year’s Under Secretary’s Award for Outstanding Achievement in Health Services Research was awarded to Dr. Donna Washington for her incredible accomplishments in the field of diversity, equity, and inclusion and women’s health. The competition was fierce as the nominees for this award are also phenomenal researchers and attests to the amazing pool of researchers that HSR&D has been honored to partner with over the years!

June 23, 2021

By David Atkins, MD, MPH, Director of HSR&D

David Atkins, MD, MPH, Director, HSR&D

As vaccinations increase and COVID cases fall, I hope many of you have felt the freedom to resume parts of your pre-COVID existence. In the past few weeks, I have bicycled into the office, flown to see my youngest son, watched a movie in a theatre, and attended live music. The last of these – the chance to convene with a group of strangers connected only by a love of live music and a particular musician (Richard Thompson, a legend of the British folk scene since the early 70’s) -- felt especially poignant. At the same time, it is also clear that our pre-COVID work world is not coming back. In the Office of Research and Development we are assessing how best to balance the clear benefits of telework (shortened commutes, less pollution and traffic, lower stress on those with parenting or caregiving duties) with the value of being together in person (ease of communication, team building). Individual VAMC’s and research divisions across VA are engaged in the same discussions. While the past year demonstrated that HSR&D researchers can work effectively in a 100% virtual environment, it didn’t demonstrate that this is the best way to work. We lose something important when we only see each other on a laptop screen. There are no serendipitous meetings on Zoom, no ducking into someone’s office at the end of the day to bounce off a new idea, no casually checking in on someone who seems a little down. At the same time, we are also realizing in ORD that a more virtual work environment, where employees don’t need to relocate to DC, could greatly expand our ability to recruit staff. We are listening to our staff carefully to try to create a “future of work” that optimizes the productivity and experience of each individual and each work unit while being equitable to all.

I had similar thoughts in attending the virtual AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting this month, the second straight year it has been virtual. The plenary sessions were excellent and offered the advantage that people could pose questions live in the chat rather than racing to a microphone. Was it significantly worse to watch speakers up close on my laptop vs. on a screen in a cavernous conference hall? The pre-recorded abstract sessions also worked well, and I loved being able to watch sessions asynchronously rather than having to choose among competing sessions. The lower cost of meeting virtually should widen access to the conference and I thought of how much lower the carbon footprint was with thousands of foregone plane flights. Despite all of these advantages, however, attendance was down again this year, for the simple reason that people prefer to meet in person. We love the chance to travel not because we love cramming into an airplane but because it is the only way to get away from the constant demands of our office and clinical duties so that we can open ourselves to learning new things. As hard as I try, I can’t carve out the same protected space when I try to attend virtual conferences from the office or from home. Equally important, they haven’t yet come up with the virtual equivalent of running into old friends on the escalator, getting career advice over dinner, or being introduced to rising young stars (or conversely, to eminent research “all stars”). The importance of forming or recharging that sense of shared purpose and community can’t be discounted. (Has a successful cult ever been formed on WebEx?)

With this background, we were glad to see the recent VA memo removing the freeze on travel. We have told COINs that they can begin holding their Stakeholder Forum meetings in-person and we are offering support for some small field-based research meetings. Although we opted for a virtual CDA meeting in the Fall, HSR&D is submitting a request for a National HSR&D/QUERI meeting for summer 2022. This will mark almost 3 years from our last meeting in DC in the midst of Washington World Series fervor. I promise I will be less distracted if we meet in July. I and the rest of the HSR&D leadership team will be resuming travel this summer provided COVID numbers keep improving. We look forward to meeting you again in your native habitat – I hope you won’t be offended if I offer you a hug on reuniting.

May 18, 2021

By David Atkins, MD, MPH, Director of HSR&D

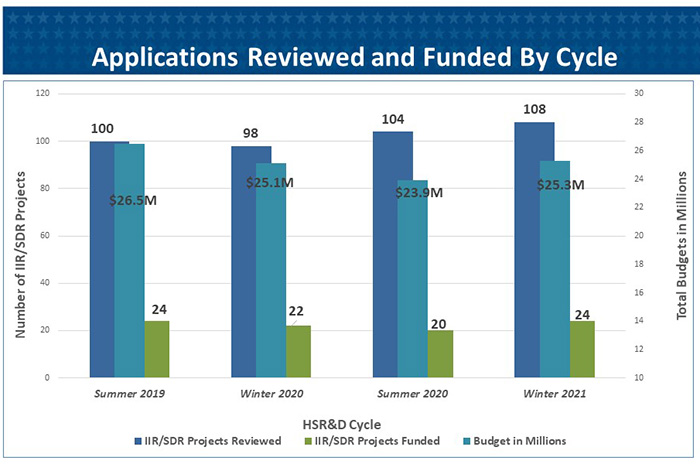

HSR&D recently completed our winter round of Scientific Merit Review Board (SMRB) meetings. The results of those meetings, in terms of projects approved for funding, are now available online. The good news is that we’ve been able to sustain a stable level of project funding for investigator-initiated research (IIR) proposals as shown in the graph. The 108 submissions and 24 projects approved for funding this last round represent our highest numbers of the last 4 cycles. The process of scientific review and funding decisions, as at NIH, consists of two steps: the scientific review, conducted by 8 separate review panels made up of VA and non-VA reviewers chosen for their scientific expertise; and an administrative review, conducted by HSR&D leadership with input from the individual scientific program managers (at NIH this function is fulfilled by their Councils).

The administrative review is intended to address several factors that may get overlooked or inconsistently addressed in the scientific review: 1) does the project significantly overlap other work already funded within VA or at NIH? 2) were there important concerns raised that are not reflected in overall scores? 3) are there time-sensitive opportunities that make funding at this time important? 4) is this project of unique value to HSR&D, ORD, or VHA priorities or, conversely, are there potential issues that may make it unlikely for the research to be scalable in VA? 5) is the recruitment plan, for clinical studies, realistic and supported by pilot data? and 6) is a 3-4 year study the most appropriate way to achieve the aims of the project? Much of the administrative review is devoted to projects which are near the funding cutoff and involve assessing whether they are ready for funding or would benefit from an additional submission. Finally, we give special attention to proposals from early investigators or in areas of particular importance to HSR&D, ORD, or VA.

The administrative review largely defers to the judgment of the scientific review experts about study design and scientific contribution, but due to the factors described above we may decide we need additional discussion with applicants. Only rarely do we choose NOT to fund a project that has scored very well in review. Such cases usually involve excessive overlap with an existing project or a judgment that there are insurmountable hurdles to the study working in VA. In one example, a study proposed to develop and test a web-based solution for prevention, not realizing that the program office had already committed to using a different federally-supported web tool. Releasing the list of projects at the early “approved for funding” stage is our attempt to reduce the problem of unwitting overlap – it can take six months or longer from approving a project for funding to completing all the regulatory steps and having the project funded and listed on the HSR&D website or grants.gov. To prevent the second type of problem, we encourage early and frequent communication with partners and are working to expand venues such as our Consortia of Research (CORes) to promote regular communication between partners and the larger research community.

Rather than deny funding to a promising project, we may require closer collaboration with partners, ask for some modifications to design, fund a component of a project, ask for an accelerated timeline, or provide funding contingent on meeting early milestones. In one case, where we had concerns that the model being tested required new staff that would not be supported by facilities or VISNs, we provided partial funding for the investigator to work with stakeholders to determine how to make their model viable. One personal observation that these discussions have reinforced is that researchers tend to approach every issue as a problem of knowledge: they believe that if only we could perfect our understanding of exactly what is happening and why, through deep quantitative and qualitative analysis, we could devise a perfect solution that everyone would embrace. The reality, I think, is that many issues in healthcare reflect the challenges of more consistently implementing what we already know. In some cases, we’ve asked investigators to compress the process of developing and refining their intervention to focus more on how to implement that intervention effectively and feasibly in practice. As HSR&D funds implementation research, we encourage investigators to think about hybrid effectiveness-implementation studies to address effectiveness and implementation at the same time. We are fortunate to have a growing QUERI program that has several training hubs that provide HSR&D investigators with guidance on designing and deploying hybrid implementation studies. Scientific peer review remains the bedrock of our research program – it’s how we prevent wasting money on bad science or chasing transient issues. We are incredibly grateful to the contributions of our volunteer reviewers and to the work of our scientific program managers, our SMRB staff, and our contractors who make the process run smoothly (see the profile of Liza Catucci who manages this process in HSR&D). Here’s to the hope that as the pandemic subsides, we may meet again in person next year.

April 5, 2021

By David Atkins, MD, MPH, Director of HSR&D

When the first day of spring arrived last month, it felt that we had just endured a year-long winter, one without trips to the office, visits with family, or children heading off to school. Far grimmer has been the toll on patients with COVID, the families mourning loved ones, and the clinicians bearing the weight of it all. The initiation of this monthly “Updates from HSR&D Central Office” is a recognition that one the of major casualties of the past year has been communication with the field as my usual venues to connect with you have all been put on hold – field visits, national conferences, and our national HSR&D/QUERI meeting.

The good news is that it seems permissible to be hopeful this spring – hospitalizations and deaths continue to decline in most parts of the country as the numbers vaccinated climb steadily. With the hope that an even brighter summer lies ahead, here are some reflections on what I learned the past year:

I truly hope and believe we will be able to put the worst of COVID behind us over the coming year, but I also know the process of fully understanding COVID will take years of work from dedicated and creative researchers. I am so proud that so many of them work in VA.