|

|

Research HighlightSystematic Review Describes Strategies for Primary Care Access Management & Most Common InterventionsIOM’s Basic Access Principles for All Settings

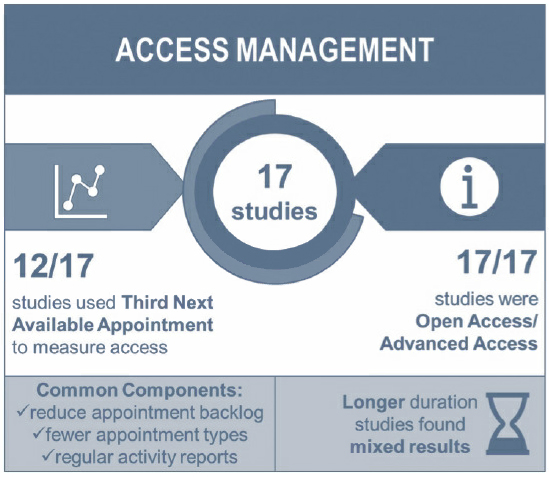

Timely access to care is expected by patients and also is a fundamental characteristic of a quality health system.1 The primary care practice setting is the most frequent point-of-care for patients, and also serves as an access gateway for mental health, specialty care, and other services. Unfortunately, little is known about the strategies employed to optimize patients’ access to quality primary care. In a recently released VA-commissioned report Transforming Health Care Scheduling and Access: Getting to Now,2 the Institute of Medicine (IOM) noted that while timely access was likely a nationwide problem, there is a lack of evidence to provide setting-specific guidance on what constitutes timely care. Nevertheless, the report described six basic principles to improve access to care in all healthcare settings. Managing primary care access requires considering many interacting system parts and goals, including continuity, team roles, and management structures. VA requested that HSR&D’s Evidence Synthesis Program (ESP) conduct a systematic review of the evidence related to primary care access management strategies so that VA might learn which interventions have been studied for which populations, and what measures are used to define success.3 ESP organized this review around five key questions and their relevant findings. For this systematic review, we searched PubMed & CINAHL for titles from 2005 through September 2016 that relate to group practice management and access, and that included studies from articles published before 2005. Included studies required the following elements: assessed primary care patients, involved an intervention to manage access, and reported an access outcome. Our literature search identified 979 titles, of which 53 publications were ultimately included. Of these, 29 assessed 19 implementations of interventions to manage primary care access—all but three were published between 2001 and 2010. Key Question #1. What definitions and measures of intervention success are used, and what evidence supports use of these definitions and measures?In the studies of management interventions to improve primary care access, the third next available (TNA) appointment was the most commonly used access metric (14/19 studies). TNA is defined as the average length of time in days between when a patient makes a request for an appointment and the third available appointment for a new patient or return visit, and it is believed to be a more stable measure of access than the first or second available appointment. However, we found no empiric data linking TNA to any health outcome. The next most commonly used access metric was continuity (seven studies), followed by patient satisfaction (three studies). We also found no evidence that these measures were associated with improved clinical outcomes. In addition to few measures of access success, many publications that discussed access management did not include a definition of access. Key Question #2. What samples or populations of patients are studied, including eligibility criteria?Patients included in published studies of primary care access management were not described in detail. In general, though, they are likely patients of primary care clinics that included family medicine as well as VA clinics. Key Question #3. What are the salient characteristics of local and organizational contexts studied?Unfortunately, little is known about the local and organizational contexts of practice sites included in published studies of primary care access management interventions. Many sites were academically-affiliated clinics, part of the British system, or in VA. Key Question #4. What are the key features of successful (and unsuccessful) interventions for organizational management of access?All the studies identified by this review described the interventions as Advanced Access or Open Access, with 15 of the 19 studies including these phrases in the publication title. The most common intervention components were reducing the backlog of appointments, using fewer appointment types, and producing regular activity reports. In eight studies reporting results of longer than 12 months duration, one study reported initial improvements in access followed by subsequent worsening, one study reported statistically significant decreases in continuity (of uncertain clinical significance), and two studies found a variable effect on access for implementations across many sites.

Key Question #5. Are relevant, tested tools, toolkits, or other detailed material available from successful organizational interventions?We identified and retrieved six tools or guides for improving primary care access, with four linked to included studies: one from a VA setting, two from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement/Advanced Access group, one from the United Kingdom’s National Health Service, and two additional online tools from Canada. A key finding of this review is that evidence about primary care access management is essentially limited to the implementation of Advanced/Open Access, with all but three publications falling in a 10-year period from 2001 to 2010. Most studies reported dramatic improvements in access. The most commonly used intervention components were reducing appointment backlog, using fewer appointment types, setting goals, and producing regular activity reports. Unfortunately, whether these are key features of success cannot be determined from the data. Some studies of longer duration reported more mixed results, with rising wait times and the need for modifications to the access management strategy reported in two large, long-term studies. This evidence-based report represents the first in a series of activities to explore unanswered questions, catalyze novel research and measurement discoveries, and ultimately result in policy changes and innovation. These subsequent activities included an expert panel process, a state-of-the-art conference, and various evaluation efforts occurring in partnership with the Office of Veterans Access to Care, Office of Rural Health, and other program offices. These activities are consistent with the principles of a learning healthcare system and will help inform efforts by VA primary care sites to improve access to care for Veterans consistent with the MISSION Act. References

|

|