|

|

Research HighlightSubstance Use and Suicide Risks in Veterans—Challenges and Opportunities for InterventionKey Points

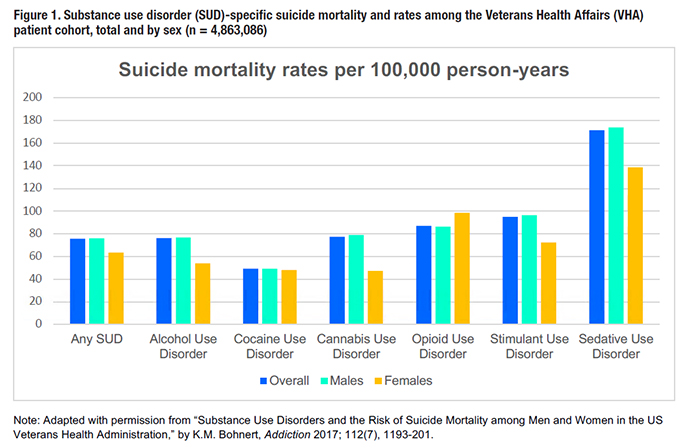

Reducing risk of death by suicide among U.S. service members and Veterans continues to be a national priority, with many initiatives focused on developing and disseminating effective treatments to those in need. Among Veterans Health Administration (VHA) patients, substance use disorders (SUDs) are strongly linked with increased risk for suicide. Consequently, VHA SUD treatment programs contain large numbers of Veterans who are at high risk for future suicidal behaviors. Implementing suicide prevention interventions in these treatment programs has the potential to play a vital role in our nation’s efforts to reduce suicide among Veterans. SUDs are common among service members and Veterans and, when present, SUDs can complicate other conditions such as chronic pain, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The research topic area of addiction has received increased attention in recent years due to the rise in opioid use and opioid-related adverse events in Veterans and the rest of the U.S. population. Suicide Risk in Veterans and Active Duty Military PersonnelAccording to the 2019 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report issued by the Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, 45,390 Americans died by suicide in 2017. Of those suicide deaths, 6,139 were Veterans, which equates to an average of 16.8 Veteran lives lost per day to suicide. Within active-duty military personnel, suicide is the second leading cause of death, surpassing both death by illness or injury and being killed in action. The Department of Defense (DoD) Task Force on the Prevention of Suicide by Members of the Armed Forces estimates that more than 1,100 members of the Armed Forces died by suicide from 2005-2009, which is an average of one soldier’s life lost by suicide every 36 hours. In addition to suicide mortality, data from the 2014 Health Related Behaviors Survey of Active Duty Personnel All Services Report indicate that over 2 percent of active duty personnel reported making a suicide attempt in the past year, which is nearly four times higher than the corresponding estimate in the general U.S. population. Almost 5 percent of active duty personnel reported seriously considering suicide within the past year. Substance Use and Suicide Risk– A Deadly CombinationGrowing evidence highlights the intersection of substance use and suicidal behaviors in military personnel and Veterans. Of the psychiatric disorders that have been linked to suicide in VHA patients, SUDs represent one of the strongest risk factors for suicide death. The rate of suicide for VHA patients with SUDs was 75.6 per 100,000 compared to a rate of 34.7 per 100,000 in the overall population of VHA patients. For an examination of how specific SUDs relate to suicide risk in VHA patients, see Figure 1. The 2019 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report also indicates that suicide rates were highest among VHA patients diagnosed with an opioid use disorder (OUD). Taken together, these results highlight the important role that SUDs play in increasing suicide risk in Veterans. A significant portion of the association between substance use and suicidal behaviors is likely due to the fact that certain substances can be highly lethal when used in larger quantities or in combination with other substances. In examinations of suicide mortality data, use of alcohol and other drugs prior to death is relatively common; the National Institute of Drug Abuse cites that substance use was involved in 30 percent of suicide deaths among members of the Army from 2003 to 2009. This pattern is more striking for non-fatal suicide attempts. According to the DoD Suicide Event Report (DoDSER) for 2017, drug and alcohol overdose was the most common method of attempted suicide during the reporting period, accounting for 55.5 percent of recorded suicide attempts that year. Due to the inherent difficulty in differentiating between unintentional and intentional overdose events, the incidence rate of utilization of alcohol and drugs as a means to end one’s life may be even higher than these rates suggest. For context, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, if the numbers of deaths from suicide and unintentional overdose were combined, that number would exceed the number of deaths from diabetes. Emerging Evidence-Based TreatmentsGiven that individuals at significantly elevated risk for suicide are overrepresented in SUD treatment, integrating suicide prevention treatment services into SUD treatment could be particularly beneficial. Existing data indicate that approximately one-third of SUD patients who died by suicide were seen in SUD specialty treatment programs in the year prior to suicide. Maximizing the positive impact of SUD treatment on suicide risk likely involves a mixture of optimizing the efficacy of SUD services while also addressing suicide risk. Relevant to both of these domains, VA/DoD has developed Clinical Practice Guidelines for SUD management and assessment and management of patients at risk for suicide. These guidelines provide recommendations to providers, outlining evidence- based treatment options for the treatment of each condition. For SUDs–primarily Alcohol Use Disorders and OUDs specifically–pharmacotherapy is strongly recommended as an effective form of treatment, in addition to the use of behavioral or psychotherapeutic treatment approaches. Specifically, for those with OUDs, these recommendations align with the growing body of literature suggesting that the most effective treatment for OUD is Medication- Assisted Treatment (MAT) with opioid agonists buprenorphine or methadone. Although several evidence-based treatments exist for SUDs, the Clinical Practice Guideline for addressing suicide risk provides fewer treatment recommendations, largely due to a lack of large-scale randomized controlled trials that examine treatments for suicide prevention. Researchers in the field of suicide prevention have attempted to close this gap in recent years, and have identified newer treatments that have been shown to be effective in reducing suicidal attempts. These include Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Suicide Prevention (CBT-SP). Prior trials of this intervention in the civilian population and a brief version of CBT-SP in military personnel have found that individuals randomized to CBT-SP have rates of re-attempt of suicide that are approximately half those seen in the control condition. However, delivery of suicide-focused interventions in low-intensity outpatient healthcare settings to individuals currently using alcohol and/or drugs is challenging because ongoing substance use can interfere with treatment adherence. Providing CBT-SP during an episode of SUD treatment is appealing as a way to reach patients during a period of relative stability. One large-scale multi-site randomized trial of CBT-SP is currently underway in VA, funded by DoD and conducted by our research team to examine whether CBT-SP can reduce suicide risk for Veterans receiving SUD treatment. More broadly, newer strategies are needed to identify Veterans with SUDs in other settings and intervene to help reduce suicide risk in this sizable and uniquely at-risk patient population.

References

|

|