|

|

Research HighlightImplementation Challenges to the Impact of Pharmacogenomic Testing in Mental HealthcareKey Points

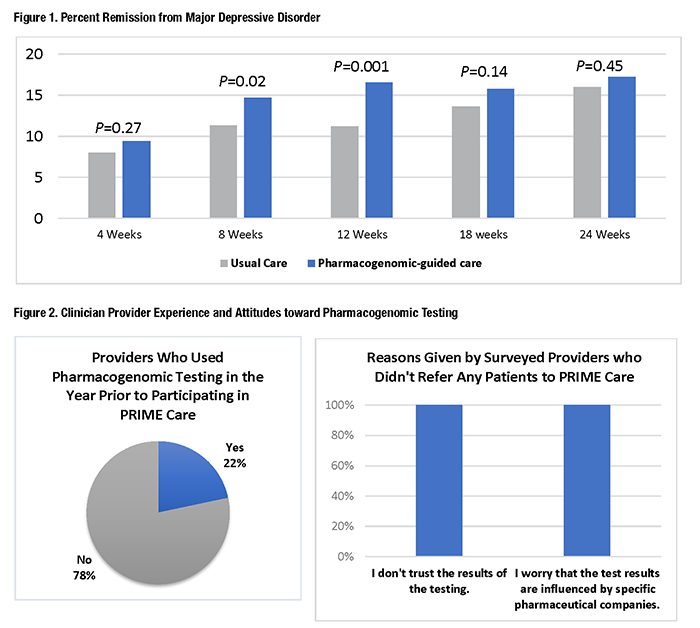

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is one of the most common conditions among Veterans receiving VA healthcare, and antidepressants, a first-line treatment for MDD, are among the most prescribed classes of medications. However, only about a third of patients treated with antidepressants achieve remission on their first treatment attempt, and the odds of success decline with each attempt. Thus, improved use of MDD treatment could have a substantial impact on Veteran health outcomes. Pharmacogenomic testing is a tool providers can use to identify medications and dosing that may best match patients’ individual genome, potentially improving medication response and avoiding adverse reactions. However, while pharmacogenomic testing has demonstrated effectiveness and has seen wide clinical adoption in fields such as oncology, evidence for its utility in psychiatry has emerged only recently. VA has been a leader in supporting efforts to study and implement precision mental healthcare. Pharmacogenomic Testing in Mental Health: The PRIME Care StudyThe VA-funded Precision Medicine in Mental Health Care (PRIME Care) study,1 a randomized controlled trial, enrolled 1,944 Veterans and 676 frontline providers in mental health and primary care settings across 22 VA sites. After the Veteran and provider determined that a new episode of MDD treatment was needed, Veterans received a pharmacogenomic test and were randomized to either receive results immediately (pharmacogenomic-guided care) or after a six-month delay (usual care). All treatment decisions, including medication choice, dose, and any subsequent changes, were determined only by the patient and provider. Research outcomes were assessed by study staff after 4, 8, 12, 18, and 24 weeks. The study found that for patients with MDD who received pharmacogenomic-guided care, the estimated risk for treatment with an antidepressant with a substantial drug-gene interaction was 11 percent. This rate was significantly reduced compared to the delayed results group, where 20 percent of patients received antidepressants with potential drug-gene interactions. Remission rates were significantly better for the pharmacogenomic-guided group, with differences peaking between the two groups at 8 and 12 weeks (see Figure 1). While the overall effect was small, a key insight was that only about 1 in 5 patients with depression was prescribed an antidepressant with substantial gene-drug interaction potential.2 Therefore, while the population-level benefit may be limited, pharmacogenomic testing could be critically important for 20 percent of patients. Challenges to Implementation and the Path ForwardAs evidence builds, VA must continue to address how to scale up pharmacogenomic testing. Among the central barriers to implementation in mental healthcare are the knowledge and comfort gaps among frontline providers about whether and how to use test results. A survey3 conducted in PRIME Care found that at the outset of the study, only about 22 percent of enrolled primary and mental healthcare providers had ordered a pharmacogenomic test in the past year (see Figure 2). Slightly more than half of mental health providers and only a quarter of primary care providers said they felt comfortable ordering a pharmacogenomic test. We also learned that only about a quarter of surveyed providers were aware that the Food and Drug Administration has revised medication labeling to include pharmacogenomic information. Surveyed providers enrolled in PRIME Care who did not refer any patients to the study unanimously indicated that they “did not trust the results of the testing” and that they “worry that test results are influenced by specific pharmaceutical companies.” Some providers worried about the ethics and safeguarding of patient privacy when handling genetics reports. These findings highlight the need for educational initiatives focused on the application of pharmacogenomics in standard practice. Providers and patients also need to understand that there are safeguards in place to guard privacy and protect against genetic discrimination. PRIME Care provided considerable educational resources for participants, including videos, talks, written materials, and one-on-one consultations. Availability of similar resources could help expand implementation across the workforce. Another potential barrier to implementation is that providers need support at the point of care, not only to ensure that they are using the information correctly, but also to help them integrate testing into their workflows. In interviews conducted for PRIME Care, providers expressed concerns about potential delays in treatment, and they worried that they would have insufficient time to properly provide education and discuss testing with patients. Influential clinical leaders and role models can help busy providers overcome reluctance and develop new workflows. A clinical decision support (CDS) platform that accommodates pharmacogenomic testing will save valuable time and maximize the value of results. However, developing the platform will require thoughtful consideration and IT and informatics investment, as pharmacogenomic information has some unique qualities. For example, unlike other laboratory results, pharmacogenomic test results are valuable throughout a patient’s lifetime, so the platform will need to provide convenient access to the information in a way that is not time dependent. In addition, most pharmacogenomic test reports are returned in formats not searchable in the electronic health record, so retrieving them can be labor-intensive. Also, approaches to genotyping and its interpretation can vary, so it is important to standardize information so that consistent recommendations are given at the point of care. With the current expectation being that routine use of pharmacogenomic testing will continue to expand, overall, the PRIME Care study has helped create a clearer picture of both the potential benefits of, and some challenges to, implementing this practice in VA mental healthcare.

References

|

|