|

|

Research HighlightHealthcare Utilization and Expansions in Access to Community CareKey Points

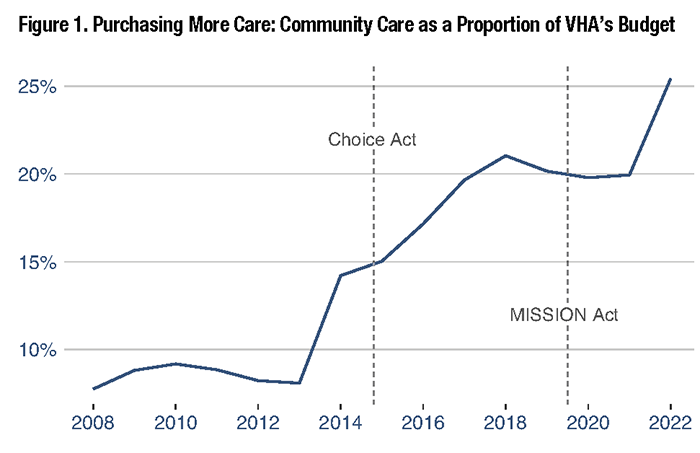

Policies implemented because of the Choice Act of 2014 and the MISSION Act of 2018 substantially increased the amount of healthcare that VA purchases from non-VA providers. However, identifying the effect of these policies on utilization, patient outcomes, and clinical care has not been straightforward. Individuals who use community care are often different from those who use VA exclusively – in ways that are both observed and unobserved. Thus, it is difficult to know if any changes over time in patient behavior and outcomes are due to these policy changes, or to other factors such as the aging Vietnam Veteran cohort, the increase in the number of OEF/OIF/OND Veteran enrollees, policy changes outside VA such as the Affordable Care Act, or the COVID-19 pandemic. What we know with certainty is that the cost of community care has increased dramatically over the last decade. Community care now consumes more than 25 percent of the total VHA budget (see Figure 1) and shows little sign of slowing down. A recent study found that this trend accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic, with VA-provided care slower to rebound than VA community care.1 However, it is unclear how much of this acceleration is due to differences between the VA healthcare system and non-VA community care, and the implementation of the MISSION Act just nine months before the start of the pandemic. To distinguish the effect of VA policies on access to community care, our study examined a specific feature of the Choice Act that helps alleviate concerns about unobserved differences among community care and VA users. Among other provisions, the law permits VA enrollees to access community care if they live more than 40 miles from a VA facility. This policy allowed us to compare enrollees around the 40-mile threshold, some of whom were granted easier access to community care. While it is not possible to randomly assign VA enrollees to be eligible for community care, this study design approximates randomization because of the arbitrary threshold. Our study found that being eligible for community care increased community care utilization by 25 percent in 2015-2018.2 Perhaps more importantly, we also found that VA-provided care did not decrease, meaning that combined VA paid and provided care increased by 3 percent. These changes were not associated with any changes in mortality. A study using similar methods examining surgical procedures also found large increases in community care utilization, but no differences in short-term mortality or readmissions.3 The significance of these findings is that expanding access to community care increases community care utilization, but not simply as a substitute for VA-provided care. The reason for this is not clear. As previously stated, community care users are different from VA-only users, and a large portion of enrollees use both community and VA care. Complicating matters further, it has long been known that many VA enrollees have other forms of health insurance. Yet, VA has long been blind to utilization outside of what it pays for or provides. Yoon et al. (2022) solved this by linking VA data with all-payer inpatient databases from several states.4 This paper showed a positive association between the Choice Act and VA community care hospitalizations, but no association with changes in mortality. Perhaps more importantly, this paper showed definitively that VA is not the primary provider of inpatient services for VA enrollees. From 2012-2017, Medicare covered more hospitalizations (54 percent) than any other payer, including VA. The significance of these findings is that much of VA’s expansion of community care can be thought of as VA expansion as an insurance provider. Because VA is required to pay Medicare rates, VA community care providers and Medicare providers are generally one and the same. The same is also true for providers that accept TRICARE and private insurance. Thus, an important open question remains: to what degree have the expansions in community care increased access to care for VA enrollees, rather than simply providing a new option for paying for the same care? As researchers, we still have a long way to go to answer this puzzle. Many studies limit their cohort to Veterans dually enrolled in VA and traditional Medicare, because VA’s data partnership with CMS allows researchers to capture patient utilization more fully. But Medicare Advantage is fast approaching 50 percent of all Medicare enrollment, and data delays and limitations have hindered examinations of this population. Moreover, such study cohorts ignore the use of TRICARE and employer-provided insurance, both of which are common among Veterans under 65. As community care becomes an increasing part of the VA landscape, it is crucial that researchers continue to find ways to examine the full set of choices Veterans face when deciding where to receive care.

References

|

|