|

|

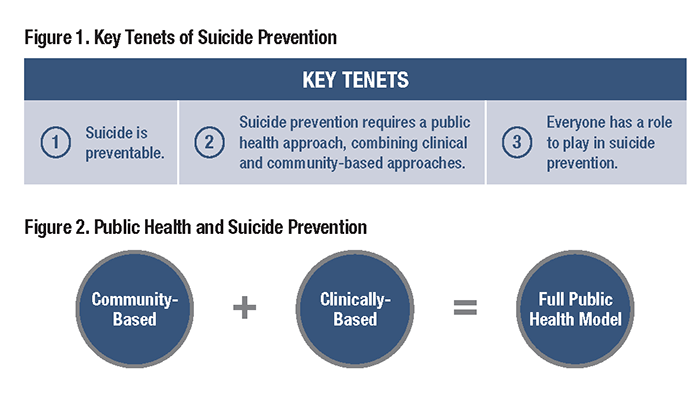

CommentaryVA Research and Operations Collaborate in Key Efforts to Strengthen Veteran Suicide PreventionThere is no single cause of suicide. It is often the result of a complex interaction of risk and protective factors at the individual, interpersonal, community, and societal levels. To prevent Veteran suicide, we must minimize risk factors and maximize protective factors at all levels of intervention. In response, VA has adopted a public health approach recommended by the National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide (2018-2028), amplified in the White House’s Reducing Military and Veteran Suicide: Advancing a comprehensive, cross-sector, evidence-informed public health strategy, with best practices codified in the VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines: Assessment and Management of Patients at Risk for Suicide (2019). Situated within the Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention (OMHSP) the Suicide Prevention Program (SPP) values the ongoing collaboration, coordination, and alignment between VA’s national research agenda, and VA’s operational and clinical priorities to address and inform Veteran suicide. SPP has numerous research questions and areas of inquiry needed to inform our community-based efforts and clinical interventions. SPP has expanded efforts to include community-based interventions. These efforts are designed to reach Veterans universally, and specifically those outside the VHA healthcare system. These interventions include partnerships with states and territories to develop strategic efforts focused on VA’s priority areas: 1) identify Service Members, Veterans, and their families, and screen for suicide risk; 2) promote connectedness and improve care transitions; and 3) increase lethal means safety and safety planning. In addition to state level efforts, VA is funding a five-year pilot project supporting the establishment of local community coalitions to advance local Veteran suicide prevention. Reviews have identified a scarcity of studies focused on community-level interventions, and evaluation of impacts and change. More research with improved methodologies and research designs is needed to evaluate multi-layered interventions, and to increase our knowledge of factors and best practices that decrease suicide risk. Previous research has shown that social determinants of health play a role in suicide risk, while mitigation of these determinants has shown protective value.1 Financial distress and cumulative stressors increase suicide risk. Homelessness, housing insecurity, food insecurity, and justice system involvement have been shown to increase risk in Veterans. We look forward to improved usage of geospatial mapping and community level data to inform where and with whom to intervene. We need evidence-informed, culturally sensitive, and responsive methods to message and reach Veterans identified by our data and surveillance to be at elevated risk. VA is the largest healthcare system in the nation to implement universal screening for suicide risk. The ‘Risk ID’ program requires annual suicide risk screening in all ambulatory clinics. All Veterans with a positive screen receive a prompt comprehensive suicide risk evaluation to inform treatment needs and options. Because suicide risk is a fluid and dynamic phenomenon, ensuring we are identifying all Veterans at risk with this method is a challenge. Simonetti et al. found that 45 percent of Veterans who died by suicide between 2000 and 2014 did not have a mental health or substance abuse diagnosis.2 Are risk assessments sensitive enough to identify suicide risk in Veterans across the numerous clinics where they present for care? How might technology inform clinical care? Research needs to include a precision medicine approach in which studies inform ‘which’ Veterans need ‘what’ interventions ‘when’. Studies focused on these areas of inquiry can help determine efficacy of risk assessment tools, the utility of technological advances (artificial intelligence, natural language processing, predictive modeling, ecological momentary assessment, and mobile applications) and the expansion of evidence for targeted interventions to support efficient and effective clinical decision making. Suicide prevention is everyone’s business, and everyone has a role to play in reducing Veteran suicide. To these ends, VA research, program evaluation, and clinical operations overlap with all areas of the VHA healthcare system, including primary care, women’s health, whole health, emergency medicine, mental health, and caregiver support, to name a few. We are grateful for the research sponsored by HSR&D that informs improved processes for suicide prevention and barriers to changes in the healthcare delivery system that impact these efforts. Further research attention on best practices to inculcate suicide prevention in VHA and community-based providers would inform our continued efforts. Additionally, suicide prevention intersects with the benefits and services provided to Veterans and their families through the Veterans Benefits Administration. To date, we have little understanding of how these benefits and resources mitigate or exacerbate risk or how they interact with other benefits, treatments, and resources to reduce suicide. We have been asked to understand and quantify the protective value of these benefits on suicide risk. Increased collaborative research with health economics would improve our ability to answer such questions. Over 70 percent of Veteran suicides are completed with a firearm.3 Securely storing firearms and medications during times of distress and crisis saves lives. We know that access to firearms increases the risk for death by suicide. However, we have much to learn to improve the application of secure storage of firearms and medications. Although secure storage has been found to be effective, resistance to secure in-home and out-of-home firearm storage is widespread. Effective messaging to Veterans has remained elusive. Further research can inform our campaigns, messaging, and strategies to amplify lethal means safety to Veterans. Training and education are a primary focus for SPP. We appreciate ongoing and continued research attention to the study of gatekeeper trainings (VA S.A.V.E), Skills Training for the Evaluation and Management of Suicide (STEMS), and lethal means safety training. Previous research has identified numerous barriers for providers across the VA enterprise to learn and incorporate suicide prevention into their routine practice. We look forward to developing and testing innovative training methods and options to address these barriers and to inculcate suicide prevention into everyday activities. Technological advances can add value to our suicide prevention efforts. Numerous innovative and novel opportunities, including use of artificial intelligence, machine learning and natural language processing, virtual reality, and computer-based assessments, are under development in the private and public sectors. However, further study is needed to determine return on investment in bringing these innovations to practice. As we know, the pace of science can be slow. SPP welcomes the opportunity and advantages of the Suicide Prevention Research Actively Managed Portfolio (AMP). We look forward to the ongoing collaboration, flexibility, and adaptability this AMP will provide to our operational priorities. We need nimble and responsive interaction between our research endeavors and our operations priorities to save the lives of Veterans. We do not have time to waste. Suicide is preventable.

References

|

|

Next ❯