|

|

Research HighlightStudy Finds More Intensive Blood Pressure Treatment Does Not Benefit Long-term Nursing Home Residents With or Without DementiaKey Points

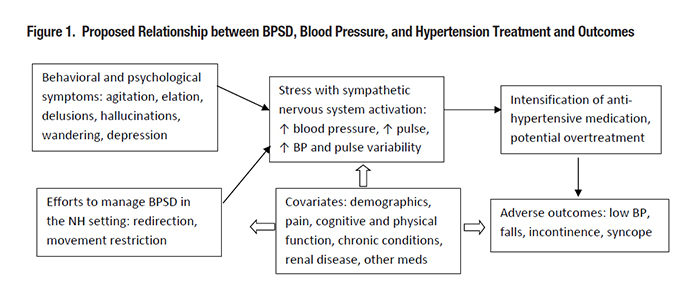

Dementia with hypertension is the most common combination of two chronic conditions in U.S. nursing home (NH) residents, affecting 27 percent of residents.1 Despite the high co-occurrence of these conditions, data is lacking to guide antihypertensive treatment intensity in this group, and there are potential benefit-harm tradeoffs. Antihypertensive medication treatment is effective in preventing cardiovascular complications, but may cause or worsen adverse events such as incontinence, syncope, and falling. In addition, antihypertensive drug administration may be stressful or a burden to patients and their caregivers. High quality evidence to guide decisions about intensity of antihypertensive treatment is scarce in this population because hypertension clinical trials do not include individuals with severe comorbid illness, disability, or limited life expectancy. In the absence of controlled trials, observational studies using large representative cohorts may help characterize patterns of antihypertensive treatment intensity in NH residents with dementia and hypertension, and provide insights into the benefits and harms of more intensive antihypertensive treatment in this population. Recent studies of ours, supported by VA’s Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care Data Analysis Center (GECDAC), The Donaghue Foundation, and the National Institute on Aging examine the associations between blood pressure treatment and outcomes in long-term residents of VA Community Living Centers (CLCs) and non-Veteran long-term residents of U.S. nursing homes. In one study, we used a cohort of long-term residents of VA CLCs to describe the frequency of antihypertensive de-intensification during scenarios suggesting hypertension overtreatment and to examine the association between antihypertensive de-intensification and subsequent falls.2 We identified 2,212 older Veterans (>65 years) who resided in 132 VA CLCs from FY2010 through FY2015, who were treated for hypertension, had a fall, and had a recent low blood pressure reading. We then identified episodes of anti-hypertensive de-intensification, defined as discontinuation of one or more first-line hypertension medications without substitution within seven days of the date of measurement of low blood pressure. We found that among these Veterans, just 11 percent underwent antihypertensive de-intensification. In addition, several hypothesized predictive factors (e.g., end-of-life status, physical function impairment, and dementia diagnosis) were not associated with the likelihood of de-intensification. Finally, antihypertensive medication de-intensification was associated with reduced likelihood of falling again in the next 30 days, suggesting that antihypertensive overtreatment contributed to falling. In a second study, we examined the association between intensive antihypertensive treatment and 6-month outcomes among 255,670 U.S. Medicare-enrolled long-term NH residents with hypertension in 2013.3 Of these, nearly half had dementia and moderate or severe cognitive impairment. At baseline, 54.4 percent, 34.3 percent, and 11.4 percent received 1, 2, and >3 antihypertensive medications, respectively. In this study, higher intensity of antihypertensive treatment was associated with slightly higher rates of hospitalization (difference per additional medication (diff) 0.24 percent; 95 percent confidence interval (CI) 0.03 - 0.45 percent) and cardiovascular hospitalization (diff 0.30 percent; 95 percent CI 0.21 - 0.39 percent) and slightly lower rates of activities of daily living (ADL) decline (decline of >2 points on a 28-point scale) (diff -0.46 percent; 95 percent CI -0.67 - -0.25 percent). There was no significant difference in mortality (diff -0.05 percent; 95 percent CI -0.23 - 0.13 percent). These associations held true whether or not the residents had dementia. Overall, one additional antihypertensive drug in each of 400 long-term NH residents with hypertension was associated with a tradeoff of approximately one greater hospitalization and two fewer episodes of 2-point ADL decline over 180 days. A 2-point ADL decline is equal to declining from requiring “extensive assistance” to “total dependence” in two ADLs. These findings suggest that long-term nursing home residents with high blood pressure with and without dementia do not experience significant benefits from more intensive treatment. In future studies we propose to explore the possibility that behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia (BPSD) (e.g., agitation) adversely affect blood pressure readings of NH residents with dementia, thereby complicating the management and treatment of hypertension in this group. BPSD is common in NH residents with dementia, affecting at least 80 percent of patients. By causing distress and sympathetic nervous system activation, BPSD likely increases blood pressure and blood pressure measurement variability (Figure 1). In addition, efforts by NH staff to manage BPSD (e.g., redirection or restriction of resident movement), and/or to obtain blood pressure measurements, might increase stress and raise observed blood pressure. NH clinicians thus must make prescribing decisions based on situational (i.e., not at-rest) blood pressure measurements, and may intensify antihypertensive treatment of patients with dementia with unlikely benefit and possible harm. To our knowledge, this question has not been previously examined. Of note, all of these studies are observational studies where antihypertensive prescribing decisions are not randomly assigned, and are related to resident clinical and other parameters. Given the known biases present in observational studies of patients with serious illness, state-of-the-art observational research methodology as well as pragmatic clinical trials are needed to define the tradeoffs of antihypertensive treatment in older adults with cognitive or physical impairment. In addition, predictive analytics might be utilized to identify sub-populations that might benefit from more or less aggressive anti-hypertensive treatment. These approaches can produce knowledge that can inform prescribing decisions for Veterans and other NH residents with dementia and hypertension, and support avoidance of overtreatment of high blood pressure in this high risk group. To help providers make prescribing decisions in this population, it is worth revisiting current treatment guidelines. The Eighth Joint National Committee on Hypertension recommends treating hypertension in adults 60 years old or older to a target of <150/90, with increasing intensity in daily dosage or number of drugs until the goal blood pressure is reached. Additional guidelines propose less intensive treatment goals in patients with comorbid conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease or limited life expectancy. Since each first-line antihypertensive pharmacologic class can cause adverse effects such as diuresis, orthostasis, falling, metabolic changes, and constipation, clinicians should always prescribe these drugs with caution and be alert to the possibility that a patient’s symptoms may be adverse drug effects. In addition, these medications are reasonable targets for de-intensification in NH residents with dementia for whom deprescribing is consistent with their goals of care.

References

|

|