|

» Back to Table of Contents

Key Points

- Technology-enabled dyadic interventions can decrease the resources needed for both patients and their caregivers, resulting in programs that are more personalized and scalable.

- The authors developed such an intervention by adapting a telephone-based, facilitated, dyadic self-management program called Self-care Using Collaborative Coping EnhancEment in Diseases (SUCCEED)1 into a self-guided, web-based version (web- SUCCEED).

Dyadic behavioral interventions are designed to support both individuals with chronic health conditions and their informal caregivers in coping with emotional and practical challenges of chronic illness self-management. Well-designed, dyadic programs can improve patients’ adherence to self-management recommendations, quality of life, and self-effcacy, while reducing hospitalization rates.2 Unfortunately, dyadic interventions that simultaneously improve outcomes for patients and caregivers are rare. Furthermore, most dyadic interventions require communication between participants and facilitators in real-time. Compared to facilitated coaching, technology-enabled dyadic interventions have the potential to decrease the number of resources needed per patient-caregiver dyad, resulting in programs that are more personalized and scalable.2

We sought to develop such an intervention by adapting our telephone-based, facilitated,dyadic self-management program called Self-care Using Collaborative Coping EnhancEment in Diseases (SUCCEED)1 into a self-guided, web-based version (web-SUCCEED). SUCCEED was theoretically derived from our Dyadic Behavior Change Model. Semi-structured interviews with Veteran-caregiver dyads and an environmental scan of existing programs allowed us to identify three core components of SUCCEED: 1) skills to manage both individual and dyadic stress, 2) skills to manage the interpersonal stress in the Veteran-caregiver relationship, and 3) skills to build a fulflling life for both Veterans and caregivers while managing chronic conditions.

Participants of our successful SUCCEED pilot study as well as Veteran and caregiver stakeholders recommended that we create a self-guided, web-based version of SUCCEED. In this current study, we describe our process of adapting the format of the facilitated SUCCEED program into a self-guided, web- based version that would deliver the dyadic content of SUCCEED.

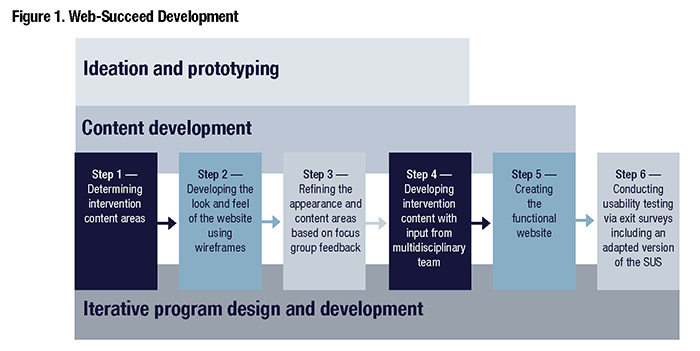

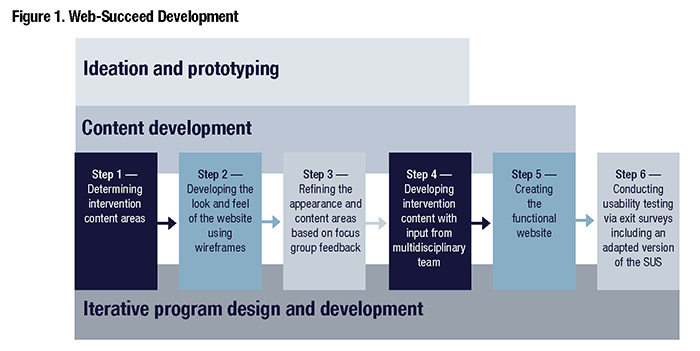

We developed web-SUCCEED in the following six steps (Figure 1).4

- Ideation. We determined content for web-SUCCEED based on the pilot test of SUCCEED, and with input from our multidisciplinary content experts.

- Prototyping. We developed the wireframes illustrating the look and feel of the

website. We ensured the accessibility of web-SUCCEED for individuals with visual, hearing, and/or motor disabilities. The PI and web designers iteratively developed prototypes that included inclusive design elements (e.g., larger font size).

- Prototype refinement via feedback from focus groups. We elicited feedback on these prototypes from two focus groups of Veterans with chronic conditions (n=13). Rapid thematic analysis identifed two themes: 1) online interventions can be useful for many, but should include ways to connect with other users, and 2) prototypes were suffcient to elicit feedback on the aesthetics; but a live website allowing for continual feedback and updating would be Focus group feedback was incorporated into building a functional website.

- Finalizing the module content and scripts. Our multidisciplinary team of content experts worked in small groups to adapt SUCCEED content so that it could be delivered in a didactic, self-guided format. Each module comprised three components: psychoeducation, skills training, and an action plan to practice skills. The fnal modules included the following.

- Introduction and How to Create an Action Plan

- Module 1: Skills to Reduce Stress and Improve Positive Emotions

- Module 2: Skills to Reduce Relationship Stress and Improve Interpersonal Relationships

- Module 3: Building a Fulflling Life and Maintaining Behavioral Change

-

Computer programming web-SUCCEED. We chose WordPress which is both Section 508 compliant and widely used

- Usability testing. Sixteen participants – evenly divided amongst Veterans and caregivers – participated in usability All participants completed at least one module and the usability survey. All Veterans were male, while all caregivers were female. Most participants identifed as White, had at least a high school education, and reported that they could afford to pay their bills. Veterans and caregivers rated web-SUCCEED high on usability, noting that the website was easy to understand, easy to use, easy to complete, and they could learn to use the site quickly. Caregivers’ mean scores on each usability item were lower than Veterans’ although we did not test for statistical differences. Verbal feedback from Veterans included “it was helpful to me,” “it was pretty easy, my wife helped me with it; I’m not that good with computers, [but] it wasn’t that hard to use,” and, “I’ve saved the URL and hope to access it in the future as a resource.” Caregivers were also positive in their feedback noting, “I thought it was pretty user-friendly,” and “overall, a good program.” Veterans noted that they would use an intervention like this and would recommend this intervention to others, and noted that if permitted, they would continue to use web-SUCCEED beyond their study participation. Most participants completed modules in multiple sittings. We found that despite being self-guided, our program required engagement of the study team to encourage completion, answer questions, and provide technical assistance.

The software development phase accounted for $100,000 in direct costs paid to the Washington, D.C.-based team including a project manager and a web designer (ideation and prototyping: $25,000; programming the website: $75,000). The other signifcant contributor to cost was personnel. Project staff (excluding PI time) involved .5 FTEE Masters’ level staff during the software development phase who served as the overall project coordinator and helped design the content and guides, and a total of 2.25 FTEE for the usability testing. All personnel were part-time on this project, which may have increased the time needed to carry out the project.

In conclusion, we successfully adapted web-SUCCEED using a systematic and rigorous process involving a multidisciplinary team of experts, Veteran and caregiver stakeholders, and human-centered design principles. We demonstrated the usability of this adapted web-based program for both Veterans and caregivers. Having dedicated, paid personnel for this project from a common source of funding may reduce both the cost and the time required to adapt existing programs into a web-based format.

- Trivedi RB, Slightam C, Fan VS, et “A Couples’ Based Self-Management Program for Heart Failure: Results of a Feasibility Study,” Frontiers in Public Health 2016 Aug 29; 4:171.

- Piette JD, Striplin D, Marinec N, et “A Mobile Health Intervention Supporting Heart Failure Patients and Their Informal Caregivers: A Randomized Comparative Effec- tiveness Trial,” Journal of Medical Internet Research 2015 Jun 10;17(6):e142.

- Shaffer KM, Tigershtrom A, Badr H, et “Dyadic Psy- chosocial eHealth Interventions: Systematic Scoping Review,” Journal of Medical Internet Research 2020 Mar 4; 22(3):e15509.

- Trivedi, , Hirayama, K., Risbud, RD., Suresh, M., et al. (In press). Adapting a telephone-based, dyadic self-man- agement program to be delivered over the web: Method- ology and usability testing. Journal of Medical and Internet Research: Formative Evaluation.

This study was funded by VA HSR&D PPO 16-139. Collaborators included Kawena Hirayama, MS, Rashmi Risbud, MS, Madhuvanthi Suresh, PhD, Marika Blair Humber, PhD, Cindie Slightam, MPH, Andrea Nevedal, PhD, Kevin Butler, PMP, Alex Razze, Christine Timko, PhD, Karin M. Nelson, MD, MSHS, Donna M. Zulman, MD, MS, Steven Asch, MD, MPH, Keith Humphreys, PhD, Josef Ruzek, PhD, and John D. Piette, PhD.

|