|

|

Research HighlightLearning from Lean Enterprise Transformation in VAKey Points

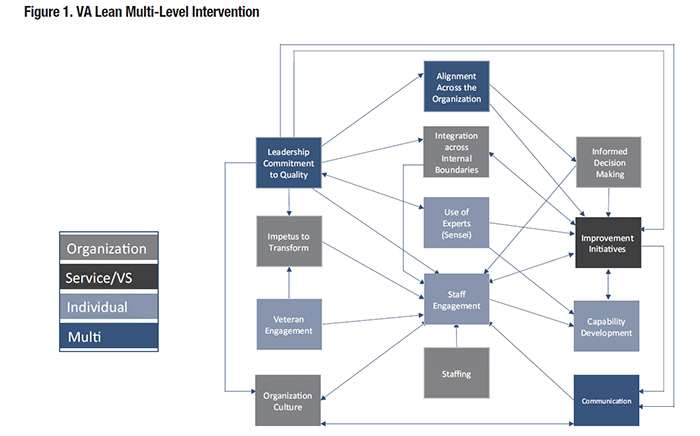

Lean thinking emphasizes standardization while reducing waste and improving processes. Various tools that together came to be known as “Lean” were first pioneered in the automotive industry and eventually spread to healthcare.1,2 Lean offers not only quality improvement methodologies but also a management system for organizations to implement change and sustain results. A Lean transformation, however, is more than just eliminating waste. It requires changing culture and embedding Lean principles into “a way of life” for the organization. In 2014, in an effort to improve quality, safety, and the Veteran’s experience, the Veterans Health Administration (VA) embarked on a pilot project, the VA Lean Enterprise Transformation (LET) program. As VA embarks on becoming an enterprise-wide High Reliability Organization (HRO), we hope lessons from the LET pilot evaluation may elucidate effective strategies to implement facilitators and reduce barriers. The LET program was designed by the Veterans Engineering Resource Center (VERC) to implement and spread Lean management tools and strategies in ten VA medical centers (VAMCs). The overarching goal of LET was organization-wide transformation, not simply implementation of individual process improvements or a set of improvements in a narrow setting. The LET program consisted of a centralized deployment strategy that included sensei (coaching) services along with programmatic and implementation support and guidance. Each site was provided two senseis. An “executive sensei” assisted the medical center’s senior executives in developing their knowledge and skills in Lean, and creating a strategy for implementing Lean. An additional sensei, together with a team of systems redesign experts local to each VAMC, helped conduct training in Lean tools and techniques for middle managers and frontline staff and provided analytic support and coaching to assist in implementing process improvements. In May 2015, the VERC, in collaboration with the VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI), initiated a Partnered Evaluation Center (PEC) to conduct a formative evaluation of the LET program. The objective of this evaluation was to understand which strategies interact to ensure successful, sustained transformation efforts and investigate how LET implementation strategies could be improved. Over the course of the four-year partnered, mixed-methods evaluation, we conducted three rounds of site visits, one in-person site visit and two follow-up telephone visits, at 6-month intervals.3 Between October 2015 and December 2017, we conducted 227 semi-structured interviews (including focus groups) representing 268 distinct key stakeholders. Interview participants included medical center directors and other executive leadership, systems redesign and process improvement directors, value stream process owners, middle managers, frontline staff, and Lean senseis. From these interviews, we learned that successful Lean implementation required several mechanisms of change, including culture change, changes in processes, leadership behavior, capability development, alignment of improvement efforts, resources, and incentives with strategic goals, and collaboration (integration).4 The multiple factors that contributed to successful transformation are depicted in Figure 1. As the figure illustrates, success requires change at various levels in the medical center. At an individual level, change can be leveraged through staff engagement, Veteran engagement, and capability development. The service line or value stream level of a medical center is where improvement initiatives typically have the most impact. Efforts to change culture, impetus for improvement, and staffing are considered organization-level. Other factors, like leadership, alignment, and communication cut across all levels of the medical center. In this article we highlight some of our key findings and comment on the relationship between the most salient factors associated with transformation and how they may vary at different levels of a medical center. Senior leadership has the most influential role in transforming culture. Using both words and actions, senior leaders must convey expectations and establish priority. Moreover, communication must be consistent and repeated, as supported by organizational change literature, and communication must be applied to all levels of management from the executive team to frontline supervisors. Where executive leaders did not convey the priority of Lean, we found that sites floundered. One successful strategy used by leaders was Gemba walks, or visiting the place where work is done. When thoughtfully planned, executed, and followed-up these walks provide managers an important opportunity to show support and reinforce the importance of Lean principles and activities directly to frontline staff, while seeing first-hand what is occurring at the frontline. Senior leaders are also responsible for aligning organizational strategy, resource allocation, goals, and personnel evaluations (corresponding to “Alignment” in Figure 1). While this is straightforward to describe, surprisingly we found it lacking in many of the sites in our study. We found many centers lacked “True North” goals. “True North” is a key concept in Lean process improvement that connotes the compass needle for Lean transformation. It might be viewed as a mission statement, a reflection of the purpose of the organization, and the foundation of a strategic plan. Ideally, True North goals are tied to measurable goals and benchmarks. At less successful sites, True North goals were absent or vaguely stated. True North was most effective when paired with metrics that were specific and tightly aligned with improvement activities. In VA, turnover in senior leadership was a challenge that interfered with senior leaders’ ability to change culture and achieve transformation. In addition to losing momentum, when new leaders joined a medical center, their priorities often differed from those of prior leaders. When this occurred repeatedly, staff developed the expectation that whatever initiatives new leaders promote will be short-lived (“this too shall pass”). Consequently, staff were less enthusiastic about new initiatives and often waited to see if shifts in priority were enduring. The most effective leaders recognize that engaging staff is necessary and critical to culture change. The complicated relationships involving staff engagement are shown in Figure 1. Staff need to be encouraged to engage in Lean. One way to achieve this is leaders directly asking managers and staff for their involvement. A second way is to clearly portray a gap in medical center performance or an aspiration for a higher level of performance that rings true to staff. In Figure 1, this is portrayed as “Impetus to Transform.” Typically medical center staff are highly motivated to improve patient care, improve patient safety, and eliminate errors; although important to the medical center, less motivating are appeals to reduce waste and cut costs. To have an effective impetus to transform, the presenting problem or aspiration has to be linked to Lean to convince staff that Lean can address the issue. This impetus to transform is usually conveyed by leadership. Articulating a motivating impetus to transform is a critical factor given staff hesitancy to become engaged based on prior experience of programs that have ended after a few months, and the challenge of multiple conflicting priorities that originate at medical center, VISN, and national levels. These compete for leadership and staff time, effort, and attention. Moreover, they have different and conflicting terminology that creates confusion. As culture transforms, not only does the expectation for staff to identify problems and identify possible solutions increase, but so does the expectation for staff engagement. One way to increase staff engagement is to involve Veterans in Lean improvement activities. Interviewees in sites with Veteran engagement expressed that they were motivated to engage in Lean improvement work for the Veteran. Staffing shortages, common in VAMCs, were an oft cited challenge to achieving staff engagement. Lean improvement activities in the form of value streams, improvement projects, and continuous daily improvement also contributed to staff engagement. In addition to the resulting improvements in processes, improvement initiatives provided an opportunity for staff training, and a positive experience that contributed to increasing expectations of the value of Lean and greater engagement. Successful improvement initiatives helped to reduce the expectation that the Lean initiative was just another fad that soon will pass. A key factor contributing to success was careful scoping of the improvement initiatives. Overscoping led to failure in several sites. Overscoping required contributions by large numbers of people over a long period of time and higher likelihood of organizational politics and lack of coordination required of multiple services or service lines. When improvement initiatives were successful, communication of this success was important for continued culture change and engagement of additional staff in subsequent improvement initiatives. Successful sites used improvement fairs, prominent displays describing improvements, posting of metrics and their relationship to medical center improvement goals, and discussion of improvements and key metrics in workgroups as well as in service/service line and organization-wide regular meetings. One of the two highest performing sites held a daily meeting to review the status of key processes across the medical center and to prioritize action items. It is important to note that training (“Capacity Building”) is a necessary but not sufficient activity. Several sites in our study that were unsuccessful in changing their culture invested substantial effort in training but did not attend to other factors. As shown in Figure 1, the impact of developing skills is realized by putting those skills into practice, which is done through improvement initiatives. The sites that were most successful encouraged staff to put their newly-learned skills into practice by improving processes. A pitfall, however, was the lack of supportive supervisors, who needed to encourage their staff, reinforce the importance of the effort, provide time and resources, and provide on-the-job training. Thus, middle managers played a key role in Lean implementation. In effective sites they actively promoted Lean and reinforced senior executive messaging. Lean and high reliability principles share many commonalities, including tools and techniques, but perhaps most important, achieving high levels of employee engagement and a change in culture to reinforce the focus on improvement, “no blame,” and encouragement of all staff to raise potential problems and potential improvements.

References

|

|