|

|

Research HighlightTowards Diagnostic Safety in High Reliability Organizations: Translating Priorities Into ActionKey Points

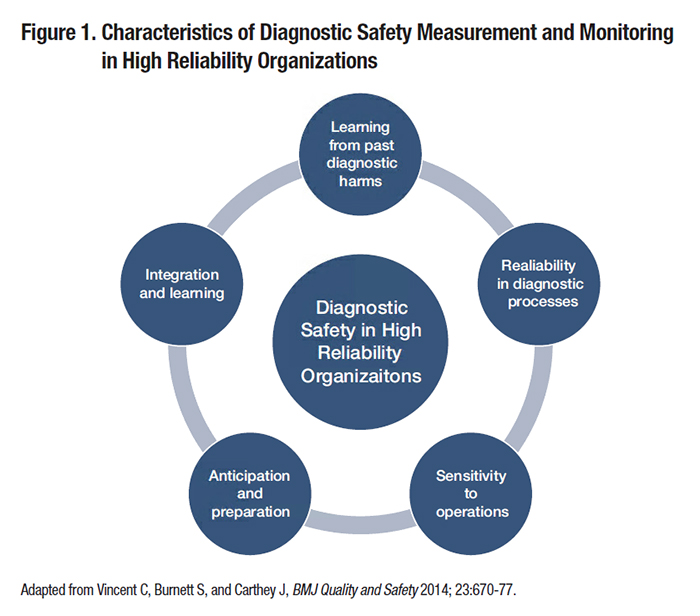

Diagnostic errors cause substantial patient harm and lead to increased costs and unnecessary utilization, yet many organizations have found it challenging to improve diagnostic safety.1 This is in part because methods to detect and measure diagnostic errors are still in an early phase of development. Diagnosis often entails a series of events across multiple dates, locations, and providers, and may evolve over the course of a patient’s care even in the best case scenario. As such, diagnostic errors (i.e., diagnoses that are missed, delayed, or wrong) can be challenging to define and even more challenging to measure reliably. Vulnerabilities in the diagnostic process may be related to numerous factors including providers, patients, and/or other components of complex, technology-enabled health systems. Amid this complexity, where to focus measurement and improvement efforts is not always obvious. Individual clinicians’ thinking and behavior influence diagnostic performance, but these factors are difficult to change, especially on a broad scale. While clinician- and patient-focused interventions are still early in their development, focusing on vulnerable systems and processes may have greater potential for impact on diagnostic safety in the near term. In this article, we describe an example of discovery translated to system-level policy and practice impacts, and discuss strategies to stimulate improvements in diagnostic safety in high-reliability organizations. Case Study: Missed Test Results as a Target for ImprovementMissed or delayed response to diagnostic test results has been identified as a frequent obstacle to timely diagnosis and a target for diagnostic safety measurement. In two of our team’s previous studies, almost 8 percent of abnormal imaging and 7 percent of laboratory test notifications in the electronic health records (EHRs) lacked timely follow-up at four weeks, sometimes even when providers had acknowledged receipt of these results. Although not all missed test results cause harm to the patient, they can increase the risk of adverse clinical outcomes for serious and/or time-sensitive diagnoses, such as cancer. In our studies of patients with newly diagnosed lung and colorectal cancers, we found evidence of missed opportunities in diagnosis, often related to test result follow-up, in 25 percent and 31 percent of cases, respectively. Informed by these and other studies demonstrating the frequency and potential harm of missed test results, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) implemented a new policy, VHA Directive 1088, to encourage more reliable and timely communication of test results. The Directive requires Veterans Affairs (VA) providers to communicate normal test results to patients within 14 days after the result becomes available, or within seven days when results require follow-up action. In 2013, VHA contracted with the External Peer Review Program to pilot test the adoption of new performance indicators on timely communication of test results. This process involved random chart abstraction and data collection to assess compliance with Directive 1088, quantified as the percentage of test results (normal, actionable, and all) in compliance, and the percentage of all test results communicated within 30 days of the report for each facility. These measures were initially pilot-tested through intensive manual record reviews and then nationally implemented. All VA facilities now have access to their data and are benchmarked. Similar processes can be used in settings outside VA. For instance, Kaiser Permanente is one of several healthcare organizations that are now launching large-scale initiatives to improve follow-up on abnormal test results. Outside VA, several health systems have introduced other initiatives to measure and improve diagnostic performance. Stakeholders such as the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the National Quality Forum, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services have committed to developing methods to operationalize and monitor diagnostic safety. Diagnostic Safety in Action: Common Principles, Many Paths ForwardDiagnostic errors are multifactorial and cannot be addressed through a single strategy, nor are there standardized metrics for diagnostic error. However, organizations can apply general principles of patient safety measurement and monitoring to learn from missed opportunities for safer diagnosis. For instance, the Health Foundation’s framework for patient safety measurement, depicted in Figure 1 and modified to focus on diagnostic safety, offers guidance for safety monitoring regardless of the specific focus of improvement efforts or metrics used.2 Implications of the framework for diagnostic safety initiatives in high reliability organizations include the following.

Actionable information on diagnostic process breakdowns may come from voluntary clinician reports, reviews of adverse events, patient complaints, or other sources. Data mining strategies, such as the use of electronic triggers applied to EHRs, may yield other unique insights into system vulnerabilities. In order to enable organizations to begin measuring diagnostic error and reduce preventable diagnostic harms, we recently co-authored an issue brief released by AHRQ as a “call to action” for achieving high reliability related to diagnostic performance.3 This resource provides pragmatic recommendations for organizations to use readily available data sources to begin to target high-risk diagnoses and diagnostic processes. At present, most healthcare organizations have few structures or processes in place to detect, mitigate, or prevent diagnostic errors. However, as our experience demonstrates, learning from errors is possible, and the outcome of this process can impact system-wide policy. A spirit of discovery and learning for the sake of improvement will inevitably bring forth much needed opportunities to enhance the reliability and safety of diagnostic processes and prevent patient harm.

References

|

|