|

The Importance of Being There for Veterans with DepressionHSR&D’s monthly publication Veterans’ Perspectives highlights research conducted by HSR&D and/or QUERI investigators, showcasing the importance of research for Veterans – and the importance of Veterans for research. In the January 2021 Issue:

|

IntroductionVeterans Engagement GroupThe Veterans Engagement Group (VEG) is a platform for Veterans to share their perspectives with other Veterans, researchers at the Portland VA, and the larger Veteran community. By joining the CIVIC VEG, Veterans can help shape the future of VA research and impact health care for all Veterans.Major depression is the most prevalent psychiatric disorder, with complications ranging from pain and fatigue, to substance abuse and obesity, to suicide. Efforts to reduce the burden of depression have largely focused on medical and psychological treatment. Less attention has been paid to addressing the social determinants of depression such as the degree to which a person is socially connected to others. Social isolation and depression have become commonplace in older adults, with estimates suggesting almost 5 percent of adults aged 50 and above lived with major depression in 2015. Factors such as reduced mobility and increased numbers of older adults living alone are major contributors. In addition to depression, this lack of connectedness has been linked to all-cause mortality and faster cognitive and physical decline. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have defined connectedness as “the degree to which a person or group is socially close, interrelated, or shares resources with other persons or groups.” More simply put, the measure of social connectedness is the quantity, quality, and manner of an individual's relationship with others. At the core of social connectedness is individual relationships among friends, family, domestic partners, shared interest groups, and other trusted members of one's social network. Research has shown that individuals with strong, supportive social relationships have lower rates of depression and severity of symptoms, and higher rates of remission. Support from social contacts has been found to be among the best predictors of help-seeking, treatment adherence, and improvements in self-care. Veteran EngagementCIVICCIVIC, an HSR&D Center of Innovation (COIN), is located at the VA Portland Health Care System. Its mission is to conduct research that empowers Veterans to improve their health through engagement in self-care, engagement with VA and non-VA healthcare systems, and engagement in the research process.Led by Alan Teo, MD, MS, a team of researchers at the Center to Improve Veteran Involvement in Care (CIVIC) designed an iterative, qualitative study incorporating feedback from the Veterans Engagement Group (VEG) at the VA Portland Health Care System. The study’s main objective was to understand how relationships with close supports (such as a spouse, or a close family member or friend) could be leveraged to improve outcomes for Veterans with depression and at risk for suicide. Thirty Veterans with major depression receiving VA primary care, and with at least one close support, participated in qualitative interviews. Interviews were semi-structured, with an interview guide based on the four broad domains of Veterans’ descriptions of close supports, their awareness and involvement in the Veterans’ depression care, barriers and facilitators to involvement, and Veteran’s preferences around an intervention to enhance involvement of close supports. The VEG met with study investigators five times over two and a half years. Feedback from Veterans prompted improvements to:

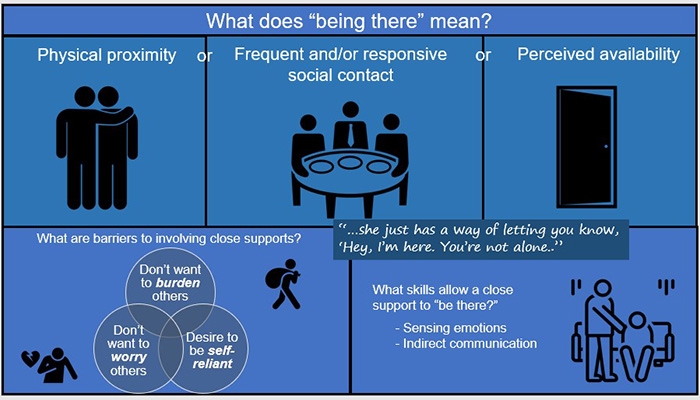

Graphic illustration of the qualities of “being there” for Veterans in this study Being ThereAnalysis revealed that “being there” was a highly valued quality of a close support to Veteran participants. This was usually in terms of availability with day-to-day life, not necessarily specific depression- or health-related events. Close supports typically provided:

“He’s just there. I can go wrap myself around him and just get a hug.”

“She’s always there for me… and if I don’t get a hold of her, she gets a hold of me.”

“I’ve never had her cut a phone conversation short, or try to put me off. She just really tries to make me feel better.” The ability to sense the Veteran’s emotional state and to communicate indirectly about it appeared to be particularly useful to being there. Shared military backgrounds or similar health problems sometimes served to inform the sensing ability, but more often close supports were described as being “attuned to” or able to “read” Veteran participants. “We just discuss what’s going on. It’s not exactly that I say I’m depressed.” “I mean, she is pretty in-tuned. We’ve been together a long time, so she reads me pretty well.” Some commonly held perceptions emerged as barriers to involvement of close supports. Veteran participants often expressed a desire not to burden close supports who had their own psychiatric or other health problems. Even when this was not the case, Veterans simply preferred not to impose on others’ limited time and availability. Three themes appeared as barriers:

ImpactThis study provides evidence of a novel way that Veterans describe, and perhaps conceptualize, their social support. Although not connected to this study, two related communication campaigns use the same theme. VA’s BeThere and the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline’s #Bethe1To reflect much of the current public messaging around suicide prevention. This study’s findings suggest that these may be tapping into a notion that is highly valued by Veterans and members of the general public with major depression who are likely to be at elevated risk of suicide.

The research team: Aaron Call, Amber Holden, Ukiah the dog, Alan Teo, Wynn Strange, and Emily Metcalf Next Steps

Alan Teo is a psychiatrist and Investigator with the Center to Improve Veteran Involvement in Care (CIVIC) at the VA Portland Health Care System in Portland, OR. He and his team study how social support and social ties--with peers, family, and others--can buffer against mental illness, and conversely how social isolation may be both a risk factor and negative outcome of mental illness.

The qualitative work in this study provides a robust rationale for developing and testing campaign messages that address Veterans’ barriers to seeking help from close supports. While prior campaigns would seem to address barriers such as Veterans’ preference for self-reliance, other barriers such as fears of burdening and worrying close supports have generally not been addressed in suicide prevention communication campaigns. This study reveals an opportunity for campaign developers to create and pretest messages targeting Veterans to counter their belief that being there is a burden or worrisome to close supports. Another endorsement centers on training for individuals who are in a position to be a caregiver or support person for a Veteran. Close supports who had mastered “being there” possessed qualities that are not simple to teach, such as an ability to sense others’ emotional needs and communicate openly but indirectly about depression. These qualities may require significant time and shared experiences to adequately develop, highlighting a challenge to creating more social support for Veterans with depression. Other research indicates that sophisticated training may be a key component to providing the skills needed to effectively support Veterans with depression. In addition to Veterans, the research team identified and interviewed seventeen friends, family members, and other loved ones who were close support individuals in the Veteran participants’ lives. Findings are being analyzed currently and will be compared to those from Veteran interviews. Dr. Teo hopes to develop and test interventions based on “being there” findings in future research projects. |