|

Peers Aid Veterans' Engagement with Mental Health Self-Care Mobile AppsVeterans’ Perspectives highlights research conducted by HSR&D and/or QUERI investigators, showcasing the importance of research for Veterans – and the importance of Veterans for research. In the July-August 2023 Issue:

|

IntroductionOne in four Veterans presenting to VA primary care suffers from one or more mental health conditions.1 Due to barriers such as time constraints on providers, Veterans’ perceived stigma, and costs associated with traveling to VA, most of these Veterans do not receive any treatment for their mental health problems.2 Mobile applications (apps) can overcome these barriers to care access. However, poor Veteran engagement can limit the use and effectiveness of mobile apps; thus, strategies are needed to boost engagement with these tools.3 To address Veterans’ challenges with access to and engagement in care, VA began incorporating Peer Specialists (Peers) into the delivery of support-enhancing interventions in 2008.4 Peers are Veterans with lived experience of substance use and/or mental illness, who are now in recovery and trained to provide services to other Veterans actively struggling with these issues. Given their recent expansion into primary care services, Peers may be an ideal workforce to facilitate Veterans’ engagement with mobile apps for self-care of mental health problems. For example, Peers can help orient Veterans to these apps and provide technical support and accountability. The use of Peers in this role aligns with other research supporting the value of using peers to increase engagement and adherence to e-health interventions more generally.5 Peers and Mental Health Apps

Dan Blonigen is an investigator and an Associate Director with the Center for Innovation to Implementation (Ci2i) in Menlo Park, CA. Kyle Possemato is an investigator and an Associate Director at the VA Center for Integrated Healthcare based in Syracuse NY.

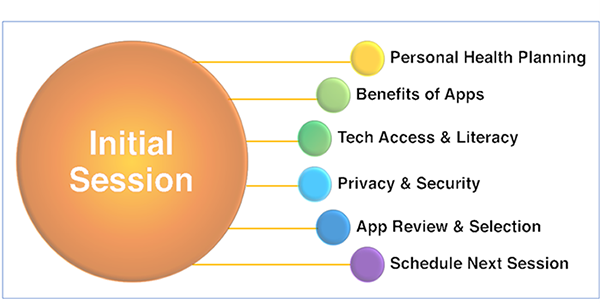

In the Implementation of Mobile Health for Veterans in Primary Care: Using Peers to Enhance Access to Mental Health Care study, investigators designed a protocol for Peers to support Veteran primary care patients’ engagement with mobile apps for mental health self-management and tested the feasibility, acceptability, and clinical utility of this approach. This study was conducted in collaboration with Integrated Services and Peer Services in the Office of Mental Health & Suicide Prevention (OMHSP). Phase 1In the first phase of the study, investigators sought to identify facilitators and barriers to using Peers to support implementation of mobile apps in VA primary care settings. They interviewed 17 Peers and 11 primary care staff from sites participating in a national evaluation of the VA Peers in PACT program. Findings were published in the Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science.6 Nearly 80% of those interviewed believed that Peers would be effective in supporting implementation of mobile apps. Support of apps was viewed as compatible with Peers’ role in supporting Veterans’ navigation of VA services, with participants highlighting both the relational benefits of Peers being able to share their lived experience and the greater bandwidth that Peers have for such a role compared to other primary care staff: “Peers can speak to their personal experience regarding using the apps or going through a certain therapy. Any clinician outside of a peer doesn’t, or probably shouldn’t, speak to their own experience… They also probably have more time than a clinician or nurse to really sit down and show the Veteran how to use it” (Primary care staff) Participants also reported that Peers introducing and supporting Veterans’ use of mobile apps was consistent with Whole Health principles in which many Peers are trained, that focus on empowering Veterans in their self-care. “The Whole Health approach has a lot to do with why health is important… and that can be converted to using an app” (Peer) Interviewees felt that it would be important for Peers in this role to highlight the benefits of the apps for self-care by sharing their lived experience with the tools the apps offer, demonstrating how the apps work, and following up with the Veteran to see if they have used the app: “I can relay how the apps have helped me” (Peer) “Peers help them troubleshoot. I think most of us need some practice before we’re good at using an app” (Primary care staff) “…Once we go over how to use the app… conducting a follow-up relatively soon would be very useful” (Peer) Participants also noted some barriers to the use of Peers to support mobile app engagement. For example, participants noted that Peers generally lack training on VA’s apps: “Lack of knowledge is a barrier… If I used it myself, I can sell or share it. If I haven’t used it, I am not able to” (Peer) A lack of knowledge of the Peer role among the medical staff in primary care was also noted as a barrier by some participants, which may impact Peers’ ability to promote apps with patients: “I don’t think a lot of providers understand the benefit of having Peers. They can’t see how the Peers can help patients better than they can” (Peer) Finally, participants reported various patient-level barriers such tech literacy or access that would present challenges to Peers supporting the patient’s use of an app: “The difficulty with apps varies depending on the Veteran(‘s) comfortability with technology…” (Primary care staff) Phase 2Guided by findings from Phase 1, study investigators formed a Steering Committee of stakeholders to guide the research team in the design of the Peer-Supported Mobile Health (“Peer mHealth”) protocol. The Steering Committee consisted of representatives from Integrated Services and Peer Services within OMHSP, Office of Patient Centered Care & Cultural Transformation, DoD’s Mobile Health Agency, and a Veteran patient from the VA Palo Alto Veteran and Family Engagement Council. Through an iterative process between the investigator team and the Steering Committee, a four-session manualized phone protocol was developed. In the initial session, Peers help Veterans to:

Session one of the Peer mHealth four-session manualized phone protocol In the follow-up sessions, Peers assess the Veteran’s app usage since the last session, discuss the content of any apps that were used, discuss the fit of the app(s) used with the Veteran’s personal health goals, provide technical support as needed, and encourage ongoing use of the app(s). Follow-up sessions tailor usage and provide support Phase 3In the final phase, study investigators conducted a single-arm pilot study to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and clinical utility of the Peer mHealth protocol. Findings were published in Psychological Services.7 Across two VA sites, 39 Veterans who screened positive for depression during a primary care visit and were not currently in mental health treatment were enrolled. They were scheduled to meet with a Peer four times and introduced to five VA-developed mobile apps for a range of transdiagnostic mental health issues (stress, low mood, sleep problems, anger, and trauma). Key findings were:

Impact and Next StepsMobile apps can only increase access to mental health treatment if patients actively engage with them. This study found strong support among multiple stakeholders for using Peers in primary care to support Veterans’ use of mobile apps for mental health problems. In this context, a brief, peer-based protocol appears feasible and highly acceptable to Veterans. However, peer support of apps may function best if it is tailored to the needs of patients over time. An adaptive intervention implemented within the context of a stepped-care model in primary care may be recommended. Going forward, the investigators will work with their OMHSP partners to develop an adaptive intervention for Peer mHealth that can be feasibly implemented across VHA PACT settings. These efforts will support VA-wide expansion of the Peers in PACT program, as described in recent legislation (STRONG Act).8 References:1 Trivedi R, Post E, Sun H, et al. Prevalence, comorbidity, and prognosis of mental health among US veterans. American Journal of Public Health. 2015. 105(102), 2564–2569. 2 Abraham T, Lewis E, & Cucciare M. Providers’ perspectives on barriers and facilitators to connecting women veterans to alcohol-related care from primary care. Military Medicine. September 2017. 182(9), e1888–e1894. 3 Reger G, Harned M, Stevens E, et al.. Mobile applications may be the future of veteran mental health support but do veterans know yet? A survey of app knowledge and use. Psychological Services. June 13, 2021. Online ahead of print. 4 Chinman M, Daniels K, Smith J, et al. Provision of peer specialist services in VA patient aligned care teams: Protocol for testing a cluster randomized implementation trial. Implementation Science. May 2, 2017 12(1), 57 5 Possemato K, Wu J, Greene C, et al. Web-based problem-solving training with and without peer support in veterans with unmet mental health needs: A pilot study of feasibility, user acceptability and patient engagement. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(1), e295.

7 Blonigen D, Montena A, & Possemato K, et al. Peer-supported mobile mental health for veterans in primary care: A pilot study. Psychological Services. September 15, 2022. Online ahead of print. 8 Takano M, H.R. 6411 – Support The Resiliency of Our Nation’s Great Veterans Act of 2022 or the ‘‘STRONG Veterans Act of 2022’’. |